More Than a Health Crisis: Covid-19 and the Backward March on Gender Equality

From the rise in gender-based violence to the lack of face masks for frontline healthcare workers, we look at how Covid-19 is hurting women the most

From the rise in gender-based violence to the lack of face masks for frontline healthcare workers, we look at how Covid-19 is hurting women the most

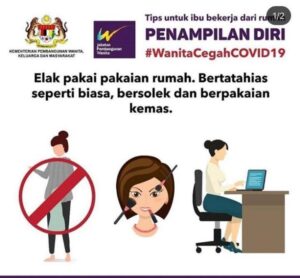

In March, the Malaysian government’s Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development put out some ‘advice’ for women trapped at home with their husbands during quarantine: wear makeup, don’t wear ‘casual or loose’ clothes, do not nag and avoid using sarcasm when your husband offers to contribute to housework. Unsurprisingly, a lot of online outrage and ridicule followed, and the advice was quickly withdrawn.

Though the internet was quick to move on from the incident, a government message advocating for a return of conservative and patriarchal gender roles is nonetheless a stark reminder that, for women, this pandemic is far more than a crisis of health.

The Offensive Poster Published by Malaysia’s Ministry for Women

Women do appear to be less biologically susceptible to Covid-19, with some speculation in the scientific community that this may be due to their having two X chromosomes. However, if we look beyond the health data and at the wider impact of the pandemic, women are far more likely to experience long-term adverse effects compared to their male counterparts. In this blog post, we apply a gendered analysis to Covid-19 and discuss the manner in which this virus has made the situation of vulnerable women – from those trapped at home with violent partners, to those trapped in unstable employment in the informal sector – even more untenable.

Gender-based violence has soared around the world

Policies of isolation have illustrated how pervasive domestic violence is in society. The pattern has been the same in just about every country. Two weeks after a lockdown is imposed, calls to domestic abuse hotlines exponentially rise. In France, cases rose by a third in the first week of lockdown, reports are up by 75% in Australia and cases have doubled in Lebanon. In Turkey, 21 women were murdered in twenty days during quarantine.

Home isolation policies amplify the power that abusers hold over their victims at a time when support services are understaffed, refuges and shelters may be closed, and the police (a limited resource at the best of times) are distracted. In addition, many forms of non-physical abuse – such as constant surveillance and invasions of privacy, isolation from friends and family, and restrictions on access to money – are all too easy to perform in a lockdown setting. Even after lockdowns are lifted, the resulting economic recession may render many women too economically unstable to escape their abusive home environment.

That stay-at-home policies would lead to a surge in domestic violence cases should have been blindingly obvious. It’s well known that gender-based violence tends to increase in disaster scenarios. This happened during the Ebola outbreak, for example.

Yet, when announcing their lockdown policies, very few governments thought it appropriate to address head on the concerns that domestic violence would increase or propose appropriate mitigation measures. In light of such indifference, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that women’s essential safety needs were nothing more than an afterthought for policymakers. We might remind ourselves at this moment that, as of February 2019, only 24.3 per cent of all national parliamentarians were women.

There has been an erosion of sexual and reproductive rights

Certain States are using the cover of the pandemic to push for policies that endanger women’s reproductive rights. In Poland, the government used the distraction of the pandemic to try to rush through a law that would have imposed even greater restrictions on abortion access. In the United States, anti-choice politicians in 8 States have succeeded in classifying abortion services as “non-essential’’ and managed to effectively ban abortion procedures along with other elective surgical procedures.

By its very nature, abortion is a time sensitive procedure – it is much safer if it takes place in the first trimester of pregnancy, not to mention the fact that many countries have laws that restrict abortions after a certain number of weeks. Nor is abortion necessarily a procedure that requires face-to-face contact. In England, Ireland and France, new telemedicine rules have enabled women to take medical abortion pills while isolating at home.

Declaring abortion ‘non-essential’ sets a dangerous precedent for how these and other (predominately Christian-far right) States and countries may continue to argue that women’s reproductive freedoms and right to health are sacrificial at the altar of ‘public health’. Going forward it may be all too easy to find other reasons loosely tied to ‘public health’ to limit these essential services further. All this will achieve is to push desperate women to seek unsafe abortion procedures, undertake dangerous and expensive travel to have abortions, or to have children when they are not in a position to be able to support them.

Women suffer more in an economic recession

As Covid-19 develops, it is clear that this is quickly evolving from a public health crisis to an economic one. The economic impact of Covid-19 is likely to exacerbate existing gender inequalities. Women are vastly overrepresented in low-paid and precarious job sectors, and the majority of the labour performed in the informal economy is performed by women. While governments contemplate spending billions to bail out multinationals in the airline and oil and gas industries, these jobs in the informal sector are unlikely to benefit from sick pay or qualify for economic assistance packages. The International Labour Organisation has already warned that 1.6 billion workers in the informal economy face “massive damage” to their livelihoods. An interview with Rendani Sirwali, a market trader from South Africa, vividly illustrates the plight of many women in the informal economy who wish to respect lockdown rules but whose livelihood depends upon face-to-face interaction.

Many women like Rendani face the impossible choice of whether to prioritise their economic needs over their health. If they do choose economic survival, they may be fined, imprisoned or deported for their actions, and can suffer societal stigma for being ‘ignorant’ and ‘ignoring’ the rules. Faced with this desperate situation, women are at risk of being pushed to accept riskier, less regulated forms of employment, where they may be at increased risk of violence and exploitation.

These structural inequalities are magnified for those who are from already marginalised groups, such as undocumented migrants, women of colour, disabled women, older women, and members of the LGBTI community, who are already more likely to be excluded from hastily assembled government relief packages.

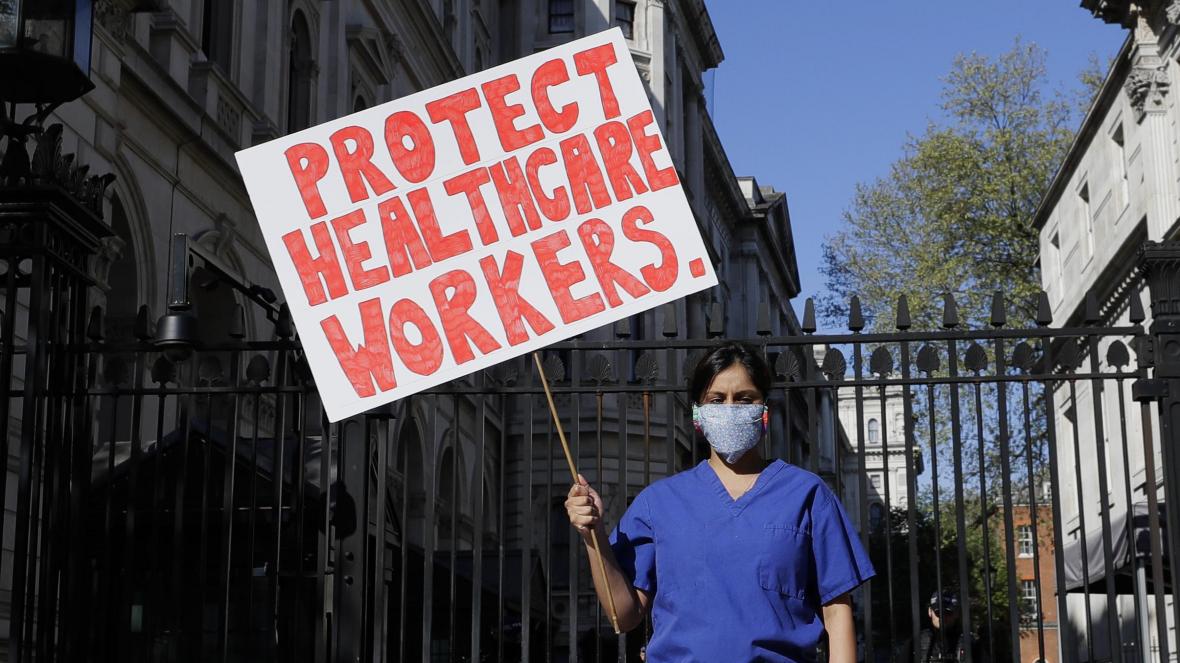

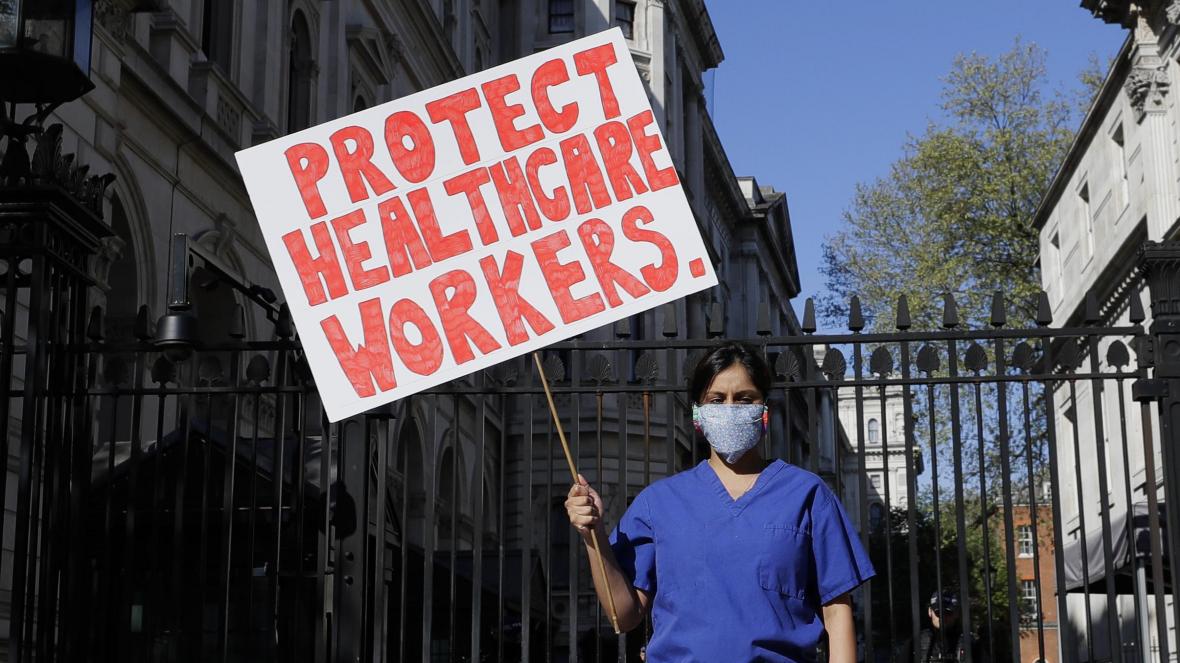

A return to ‘business as usual’ is not good enough

Women everywhere are putting their bodies on the line to blunt the force of the epidemic. Women make up 70 percent of the global health workforce, which includes not only the front-line health workers fighting the virus, but the health facility service-staff who clean and maintain the hospitals as well. Despite the risks involved in this type of work, this is some of the most systematically undervalued – and underpaid – work in our society today. Take the unpaid care work sector, where women perform three times more work than men, often while juggling paid responsibilities, but receive no compensation in return. Or consider also the fact that most ‘standard’ size personal protective equipment (PPE) is not even designed with women’s face and body shape in mind, understandably leaving the women carrying out critical frontline work with the feeling that their lives and health are simply not worth the investment to protect.

The Coronavirus crisis has revealed some profound and uncomfortable truths. One being the hypocrisy of deeming certain types of work ‘essential’ but not valuing the individuals carrying out this work enough to adequately compensate them or provide them with proper protective clothing. On the other hand, as activists we might have been pleasantly surprised by the revelation that governments are actually capable of acting quickly and decisively to designate new national priorities when they need to.

The window of opportunity to advance social justice is always a narrow and elusive one. Too many past crises, from natural disasters to financial ones, have only served to entrench the position of powerful elites and deepen existing inequalities. There is hope that the global scale of this crisis, and the sense that we may be at an endroad in terms of fixing a broken and unequal economic system, might serve as a serious wake up call for governments. As humanists, we should always make demands for a world that is oriented around human rights, but we should especially do so now, at a time when new political priorities are being set and different visions of the future are being forged.

To rebalance the scales of a global economic system is no easy feat. Perhaps we can start by inspecting the new budgets and economic relief packages proposed by our governments. Do they include funds for struggling domestic violence and reproductive health services? Do they include compensation for women’s work, particularly for women in marginalised communities? Do they boost the wages and welfare of the many workers who never stopped working to clean the hospitals, the care homes and the government buildings during this crisis? If not, let’s be ready to make our dissent clear.