After years of wrangling back and forth, and in the face of significant pressure from international partners, President Yoweri Museveni last week (24 February) gave his assent to the Anti-Homosexuality Act. This marks the final approval necessary to create a new law.

The UN Human Rights chief Navi Pillay swiftly condemned the Act, saying:

“This law violates a host of fundamental human rights, including the right to freedom from discrimination, to privacy, freedom of association, peaceful assembly, opinion and expression and equality before the law – all of which are enshrined in Uganda’s own constitution and in the international treaties it has ratified.”

LGBT and other human rights campaigners in Uganda and around the world are deeply concerned that the draconian law creates a sweeping new crime in terms so broad that could be used to prosecute any actively gay person, as well as being a gift to anyone who wants to make a malicious accusation. In addition it raises the threat of “mob” vigilantism and a massive crackdown on civil society organizations and individual advocates of LGBT rights.

IHEU considers that these are all serious and sound concerns with a strong basis in reality and condemns the law outright as “scapegoating sexual minorities, and representing a full-blown act of state persecution.”

Given these circumstances it is important to consider the law and the circumstances in detail. The draft Bill, key amendments and final text of the Act can be found via Parliament Watch Uganda.

The Anti-Homosexuality law

Death penalty removed

Introduced in 2009 by David Bahati, a Ugandan MP with links to US evangelicals including Scott Lively and “the Family”, initial drafts of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill proposed a death penalty for crimes of “aggravated homosexuality”.

The “aggravated” charge applied in cases where an HIV-positive partner had sex with someone of the same sex, but also in very ordinary cases, including a second offence of ordinary same-sex sexual activity. This meant someone could have been eligible for a death sentence, if found guilty merely of consensual sex with an adult partner on more than one occasion. For this reason the Bill earned its media nickname, “the kill-the-gays bill”.

The death penalty has since been deleted by amendment and replaced with life imprisonment. David Bahati, who is quoted as having said that he wanted “to kill every last gay person”, welcomed the signing of the Act, even though it now lacks the death penalty that he had proposed.

Life in prison for “touching” and other normal, consensual sexual activities

The terms of the new law however were only reduced to “life in prison”. In addition this life sentence now applies not only to “aggravated homosexuality” but to all acts of “homosexuality” as defined in the Act.

Those convicted are “liable” to a life sentence, and there is no other, lesser sentence provided for in the Act for crimes of “homosexuality”. The sentence on conviction is stated as “life imprisonment” with no conditions or considerations stated under which this sentence might be lessened.

The Act states that the “offence of homosexuality”, punishable by a life prison sentence, includes cases where someone sexually penetrates or sexually stimulates someone of the same sex, or simply if “he or she touches another person with the intention of committing the act of homosexuality”.

“Touching” is defined very broadly, to include touching “(a) with any part of the body; (b) with anything else; (c) through anything”.

This is clearly completely restrictive on normal, consensual homosexual acts, and additionally the scope for malicious accusation (for example if multiple parties claim to witness an act of sexual solicitation that is as simple as a touch) is abundant.

People are under no obligation to report homosexuals to authorities

Earlier drafts of the bill contained a clause on “Failure to disclose the offence of homosexuality”. There was widespread concern that this would create an obligation on individuals to report people they suspected were gay to the authorities.

This clause was deleted. No one is forced to “report” their gay friends, family or neighbours to the police. Government and the police authorities have seemingly not stressed this deletion at all in the days before or after the signing of the bill.

Threat of mob vigilantism

Furthermore, IHEU is concerned that there are good reasons to fear “mob” actions against people suspected of being gay.

Campaigners have long been concerned that the national publicity around the Anti-Homosexuality Bill stirred up hatred against gay people, and is widely attributed as the motivation behind the murder of activist David Kato.

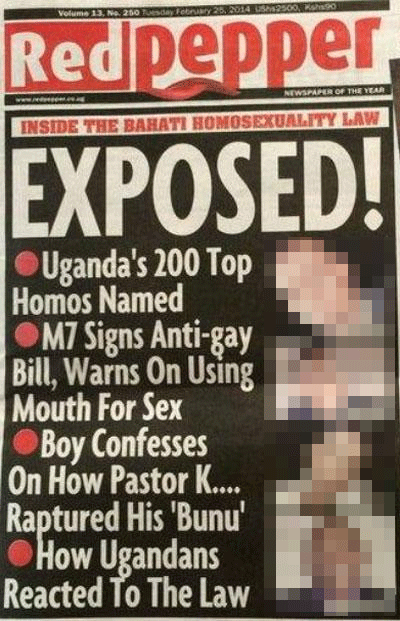

In the days after the signing of the Act, Red Pepper published a list of persons known, perceived or rumoured to be homosexual, under the headline “Exposed! Uganda’s 200 top homos named”. The United Nations criticised this as a blatant risk to incitement of violence and as violating the right to privacy and dignity of the individuals listed in such a context. The Ugandan authorities have not been so outspoken in criticising the publication.

IHEU considers that the risk of “mob justice” or vigilantism is real and current: an Anti-Pornography law given assent one week previous to the Anti-Homosexuality law prompted attacks on women in clothing that the attackers deemed inappropriate. The Uganda Police Force in this case made a statement clarifying that the law did not “ban miniskirts” and that attacks on women or attempts to strip them of their clothing were themselves criminal assaults. (The press locally and internationally have widely referred to the law as a “miniskirt ban”, in part due to the Minister for Ethics, Simon Lokodo, who has given mixed and contradictory messages about it; however the clothing that individuals might wear on the street is in no way part of the final Anti-Pornography Act.)

Despite this careful warning on the anti-pornography law, and despite concerns about vigilantism being widely voiced, at the time of writing the Uganda Police Force has made no similar statement clarifying the Anti-Homosexuality law nor warning that against attacks on gay people or anyone perceived or accused of being gay.

Threat of malicious accusation

The myths of gay “recruitment” and the erroneous conflation of homosexuality with paedophilia, pervade Uganda (myths widely repeated in all countries where homosexuality is illegal). Accusations of forced “sodomy”, or “mercantile” youths being bought for gay sex, are made at a disproportionate and unrealistic level, and a high profile case of a number of pastors accusing another pastor of “sodomizing” his congregation has been in and out of court (and the media) since 2009.

Given this background there is a serious risk of malicious accusations used to settle scores, damage reputations, and so on.

Threat to civil society and LGBT rights advocates

Groups and advocates of gay rights may be in serious trouble regardless of their sexuality. Under “promotion of homosexuality” the Act criminalizes (among other things) anyone who: “funds or sponsors homosexuality or other related activities” (other related activities is left entirely undefined); “offers premises and other related fixed or movable assets for purposes of homosexuality or promoting homosexuality”; or who “acts as an accomplice or attempts to promote or in anyway abets homosexuality and related practices”.

Clearly this could be interpreted broadly enough that advocating gay rights could be considered a “related practice” which promoted or abetted homosexuality.

Response

The LGBT activist Frank Mugisha and others have said the law can and will be challenged as unconstitutional in the courts. However concerns about the strength and independence of the judiciary and the significant social and political pressure mean that a legal challenge may be prejudiced from the beginning.

An anonymous contact in Uganda told IHEU:

Before the bill came into law many, like me, were advocating against the bill, conversationally or in public. We came to know we were many in this struggle. But immediately when the Act was signed all of us were gripped with fear, and many have fallen silent. This fear is understandable, it’s the the kind of fear that makes you fail to think of what next, what happens to my phone, e-mail and Facebook accounts because there is a great possibility that the government will now hunt us down for having raised our voices. The situation is tense, the churches are jubilating. I feel terrible. My worry is how government will crack down on its targets, and that all decisions in the courts of law are influenced by the president.

IHEU president Sonja Eggerickx said, “We condemn Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality law for scapegoating sexual minorities, and representing a full-blown act of state persecution. It is a breach of fundamental rights and entrenches ignorance and falsely validates insidious myths about gay people. We hope the law will be challenged as a breach of the country’s constitution on the grounds of discrimination and for breaching fundamental rights, and we can hope it will be repealed, but the outlook is grim.”