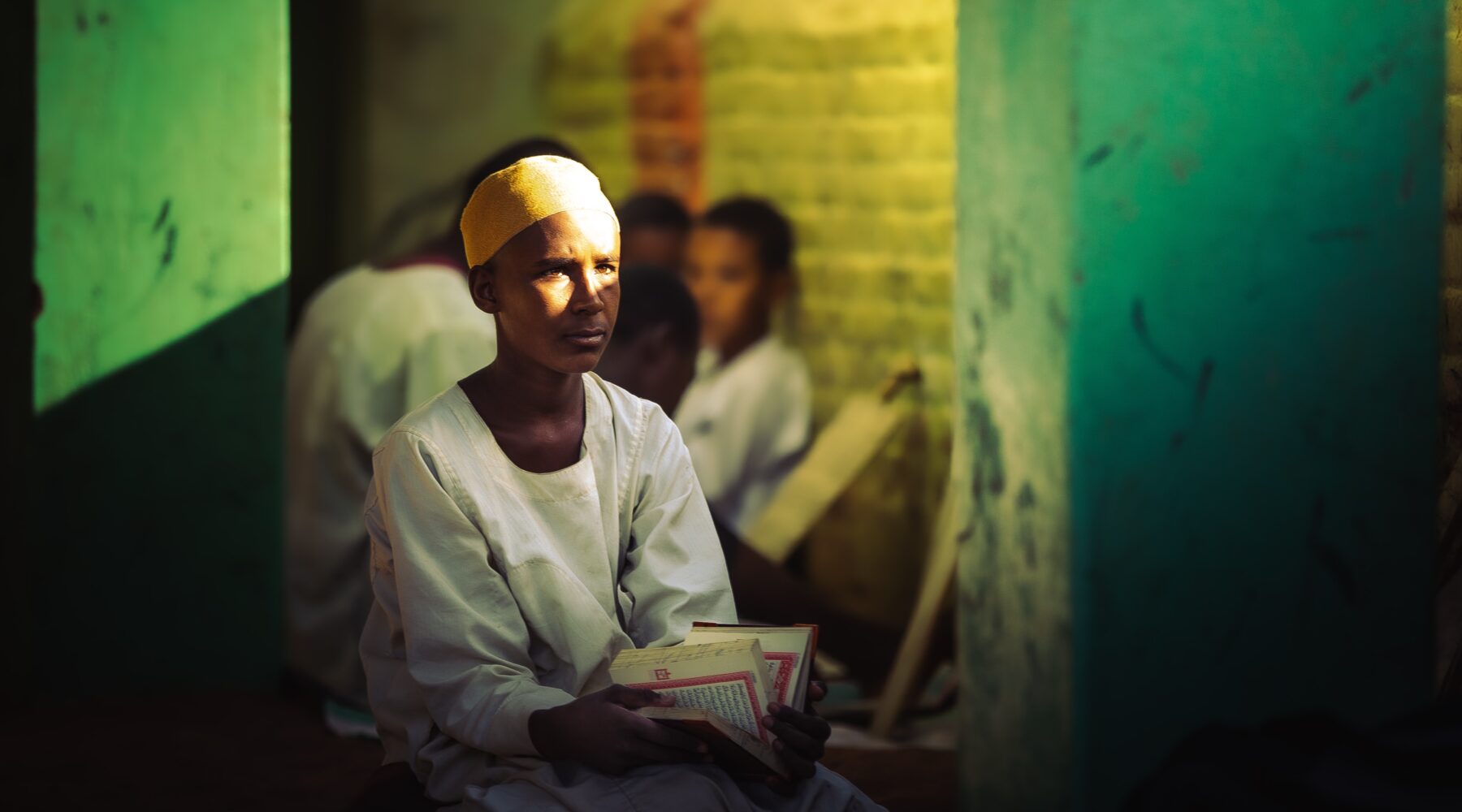

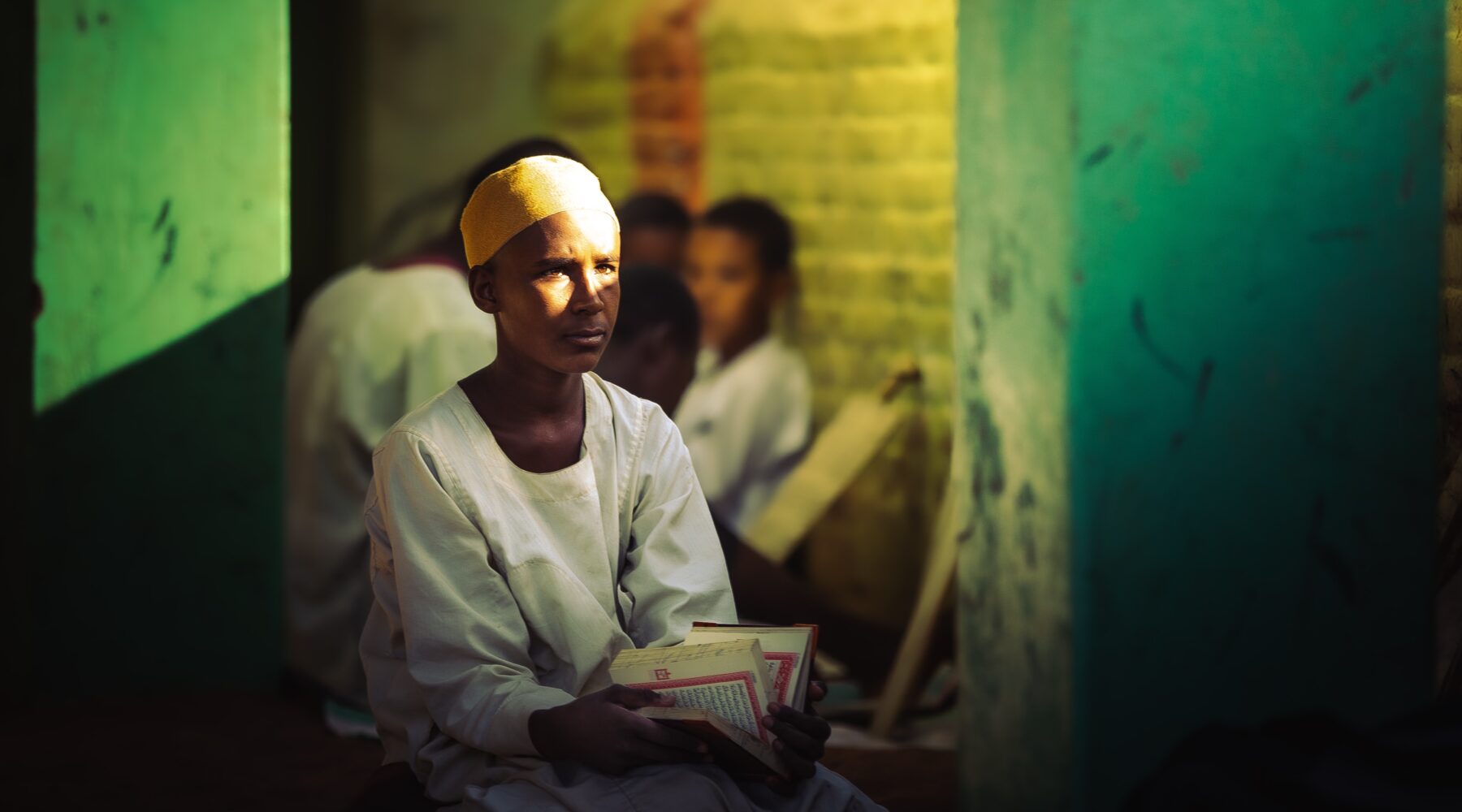

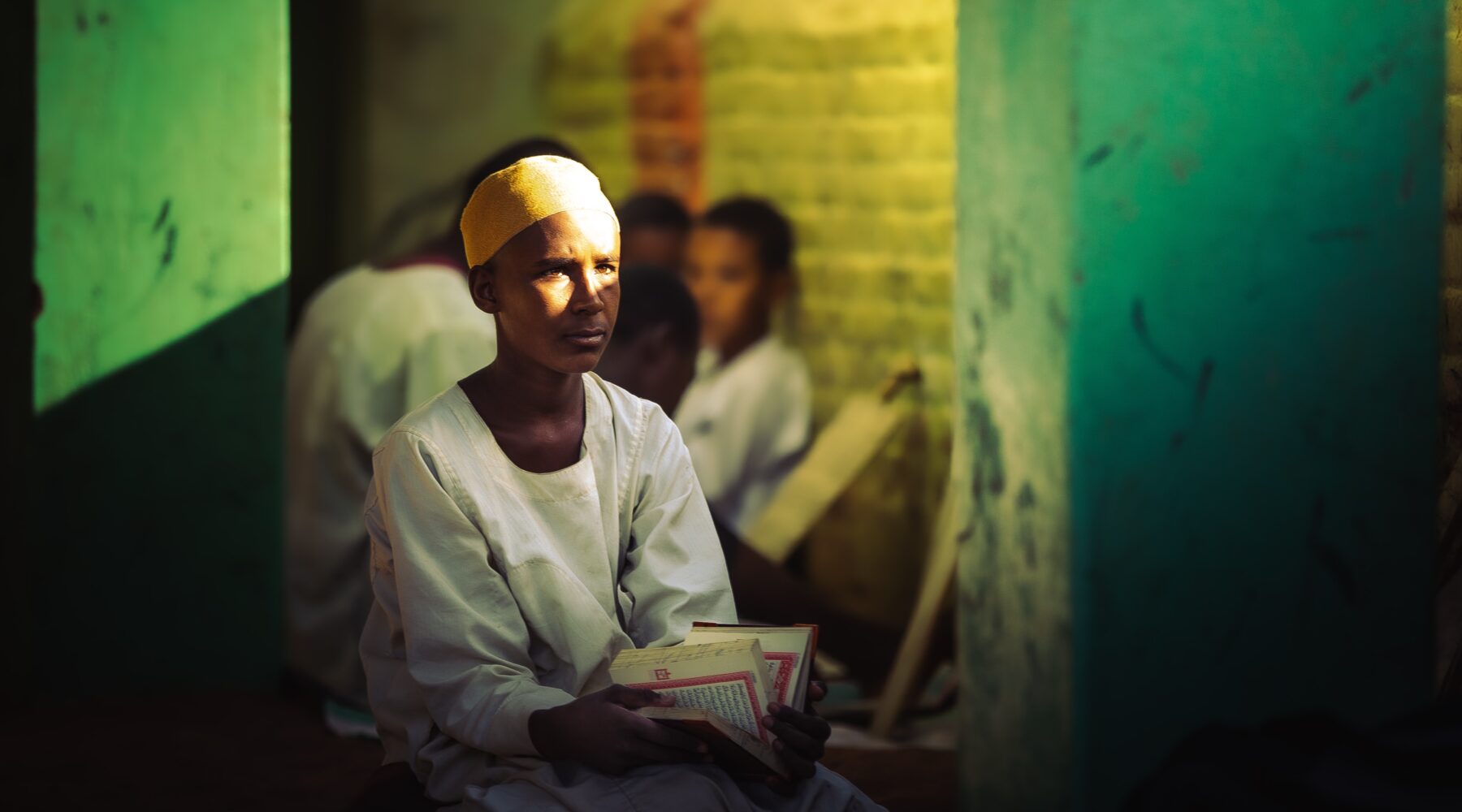

Sudan’s progressive reforms are a watershed moment for a country notorious for its historic disregard for freedom of religion or belief

In March, we reported that the Sudanese transitional government planned to abolish the death penalty for the crime of “apostasy.” As Ahmed Shaheed, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, commented to Humanists International at the time, “under no circumstances could the death penalty ever be applied as a sanction against conduct whose very criminalization violates internationally protected human rights.”

The bill containing a raft of progressive reforms to Sudan’s 1991 Criminal Code has now been signed into law. The changes represent a promising step forward in a conservative country which has tended towards strict limitations on freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression. Sudan’s criminal laws are influenced by Shari’a Law and were originally enacted by former President Omar al-Bashir, who was deposed last year after nearly three decades of rule.

Until recently, Sudan was actively pursuing apostasy prosecutions. In May 2017, 23-year old activist Mohammad Salih was arrested after requesting that his religion on his national identification card be changed from Islam to “non-religious”. His case was only dismissed after Mohamed was found ‘not mentally competent to stand trial’. In 2014, Mariam Yahya Ibrahim narrowly escaped the death penalty after she was charged with apostasy and adultery for marrying a Christian man.

What the reforms address and what they leave out

By repealing the death penalty for the crime of apostasy, ending the use of public flogging as a form of punishment, and allowing non-Muslims to consume alcohol, the new reforms mitigate some of the most extreme aspects of the Shari’a Law-influenced criminal justice system.

In a significant victory for Sudanese women’s rights, the government also announced the outlawing of female genital mutilation and an end to the requirement for women to seek permission from male members of their families to travel with their children. This followed on from another key win in November: the repeal of a strict public decency law which placed restrictions on women’s behaviour in public spaces, including criminal penalties for ‘indecent dressing’ or dancing. Thousands of women have been sentenced to floggings under these public decency laws, with poor and minority women particularly affected. Women have been at the forefront of campaigns to reform conservative and discriminatory aspects of Sudanese society. They led the protests that ended al-Bashir’s rule, with some estimates stating that they made up 70% of demonstrators.

Humanists International’s 2019 Freedom of Thought Report ranked Sudan 9th worst country in the world in terms of respecting the right to freedom of religion or belief for the non-religious. These progressive reforms mark the beginning, and not the end point, of Sudan’s efforts to bring its legislative framework in line with international human rights law and to promote a more inclusive and representative society.

As part of its reform movement, it is imperative that apostasy and ‘religious insult’ (currently an offence under section 125 of its 1991 Criminal Code) are both decriminalised in full, so that Sudanese citizens of all beliefs are free to express themselves on matters of religion in accordance with international law and standards. As many Sudanese women have expressed, signing the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and outlawing child marriage should also be a priority for the government, given that one in three women are ‘legally’ married before the age of 18 under Shari’a Law.