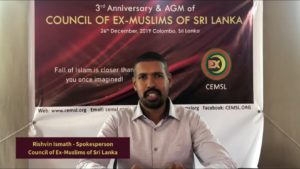

Rishvin co-founded CEMSL in 2016, three years after leaving Islam.

Founding President of the Council of Ex-Muslims of Sri Lanka, Rishvin Ismath, has been the target of sustained threats since 2016. In June 2019, Rishvin’s identity as an ex-Muslim was made public when he appeared before the Parliamentary Select Committee established to investigate the April 2019 Easter Sunday suicide attacks. The threats he received forced him to relocate for his own security. Despite relocating, Rishvin has continued to receive threats, both in person and through social media.

In his own words

History of the case

2021

Rishvin continues to live in hiding as a result of the danger he faces from Islamist extremists. He continues to receive threats on a regular basis.

2020

On 26 August 2020, Rishvin reported that a threatening letter had been received at his home address to which he has not returned since 2019.

On 8 October 2020, Rishvin was approached by a man who refused to identify himself, who threatened him if he failed to seek permission to cross examine indicted former top-ranking police officers before the Presidential Commission of Inquiry on the Easter Sunday Attacks.

Upon the close of a session of the Commission held on 26 October 2020 in which Rishvin participated by questioning Rasheed Hajjul Akbar about his role in propagating Islamist teachings and violence in Sri Lanka and abroad, Rishvin was threatened by two known associates of Hajjul Akbar, who were waiting outside the building.

Judges ordered an inquiry into the threats and instructed the Authority for the Protection of Victims of Crimes and Witnesses to provide Rishvin with all necessary security. Rishvin reported the incident to the police. To date, no action has been taken by the police.

2019

Rishvin reports that he was visited by members of the Terrorism Investigation Division (TID) on multiple occasions throughout May 2019. Officers informed Rishvin that members of a local ISIS group were trying to kill him.

In June 2019, Rishvin’s identity as an ex-Muslim was made public when he appeared before the Parliamentary Select Committee to highlight the dissemination of Islamist extremist messages in school textbooks. The threats he received forced him to relocate for his own security. Despite relocating, Rishvin has continued to receive threats, both in person and through social media. He has, as such, had to limit his movements out of doors to the bare minimum.

2018

Rishvin establishes his blog (www.allahvin.com)

2017

In July 2017, Rishvin made a complaint to the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) about fresh death threats, providing evidence.

In August, Rishvin is forced to file a second complaint with the CID regarding threats he has received, including all relevant evidence.

Rishvin reports that he was forced to limit his activities for his own protection following the failure of the police to address his complaints.

2016

In July 2016, Rishvin filed a complaint with the Terrorism Investigation Division (TID) regarding death threats he had received and raising concerns related to suspected ISIS activities in Sri Lanka. Several of the individuals he identified in his statement have subsequently been connected to acts of terrorism, including the Aliyar Junction Clash and the April 2019 Easter attacks that resulted in the deaths of at least 250 people.

2014

Rishvin begins publishing constructive criticism and posts questioning Islam on social media.

2013

Rishvin leaves Islam.

Background information

Rishvin has played an active role in the humanist community since 2016. He is the co-founder of Humanists International’s Associate organization, the Council of Ex-Muslims of Sri Lanka (CEMSL). After leaving Islam – the faith he was born into – in 2013, Rishvin began working constructively to challenge harmful religious beliefs and practices. This activity culminated in the founding of CEMSL, and his work to expose threats of Islamic extremism. As a direct result, has been the target of sustained threats ever since.

Rishvin is a dedicated activist, working in coalition with a range of actors on human rights issues both at home and abroad.

Country background

The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka is a country of just over 20 million people occupying an island in the northern Indian Ocean. Formerly part of the British Empire, “Ceylon” attained independence in 1948, and became a republic in 1972. There are many ethnic groups on the island and Sri Lanka’s post independence history has been marked by ethnic violence.

The Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

According to the Constitution, every person is “entitled to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, including the freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief of his choice.” The Constitution gives a citizen “the right either by himself or in association with others, and either in public or in private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice, or teaching.”

Four religions are recognized by law: Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism and Christianity. However, the Constitution also accords Buddhism the “foremost place” and commits the government to protecting it, but does not recognize it as the state religion. Atheism is not recognized by the state.

Legal Framework

The Criminal Code under article 290 prohibits injury or “defilement” to places of worship, and under article 291 the “disturbance” of worship. 290A further criminalizes any act in a variety of circumstances within or near places of worship which is intended to “wound religious feelings” or may be considered an “insult” to religion. Moreover, the law goes on to criminalize in very broad terms any act, including speech acts and written words, made with the intention of “wounding the religious feelings of any person” (article 291A) or “outraging the religious feelings of any class of persons” (291B), respectively. These are all imprisonable offences.

Article 3(1) of the ICCPR Act 56 of 2007, states: ‘no person shall propagate war or advocate national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence’ and makes any such crime a non-bailable offence which is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. Sri Lanka’s ICCPR Act 2007 falls short of international standards guaranteeing the right to freedom of expression.

Together with the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act No. 48 of 1979 these articles form the basis for Sri Lanka’s legal framework to combat hate speech.

Following a recent country visit, Ahmed Shaheed, UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, noted that: “civil society has observed that certain actors have attempted to misuse the ICCPR Act to restrict freedom of expression and crush dissent. Although inciting to discrimination, hostility and violence is criminalised under the ICCPR Act, many argued that the Act was not applied in a manner that would protect minorities against incitement; rather, it is invoked to protect religions or beliefs against criticism or perceived insult. ICCPR Act has ironically become a repressive tool curtailing freedom of thought or opinion, conscience and religion or belief.”

Humanists International is aware of several cases of individuals peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression or belief who are facing complaints under Article 291(B) and 3(1) of the penal code and ICCPR Act, respectively.

Lived experience

According to Humanists International’s Humanists at Risk: Action Report 2020, Humanists and atheists in Sri Lanka face significant social stigma and discrimination.

One of the most difficult things for non-religious people is to gather in public with like-minded people. One respondent to Humanists International’s survey stated:

“Humanists can have gatherings and meetings only for a selected crowd at in-house auditoriums (subject to the permission of the management). Arranging a large public gathering or meeting is not possible as there could be troubles created by Buddhist monks. Particularly, ex-Muslims have no way of gathering in public, whether small or large, their safety and privacy would be at high risk. Ex-Muslim gatherings are always secret.”

Humanists International’s concerns and calls

Taken together, these incidents suggest that his current strategy of internal relocation and isolation, going out only when necessary, are no longer sufficient to ensure Rishvin’s safety. To date, the relevant authorities have failed to take steps to safeguard his well being, and Rishvin has an understandable fear that he has no further recourse for protection within his homeland.

Humanists International believes that Rishvin is being targeted solely for peacefully exercising his rights to freedom of religion or belief and freedom of expression, as a result of his work to combat extremism and promote tolerance, and calls for the Sri Lankan authorities to investigate these threats and ensure Rishvin’s safety.

Humanists International’s work

Humanists International is providing ongoing advice to Rishvin while he remains in hiding for his own security.