After calling out France at the UN for rhetoric used by many of its officials during the ‘burkini’ debate, IHEU director of advocacy, Elizabeth O’Casey, blogs about the reasons she thought this an important issue for an organisation like the IHEU to raise at the Human Rights Council.

For my first intervention at the 33rd session of the UN Human Rights Council, I raised the issue of secularism in the context of anti-extremism policies – and with specific reference to France and Central Asia. I was keen to discuss how some states have been dealing with extremism by instrumentalising and distorting the concept of ‘secularism’ and undermining the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of religion or belief. Following on from our statement on secularism in the midst of the burkini debate in France, I thought it was important that we speak about the issue at the Council also.

IHEU Director of Advocacy, Elizabeth O’Casey, speaking at UN

At the IHEU we work hard to promote the right to freedom of thought, religion or belief and the right to free expression for everyone – whatever they believe, whatever they say (obviously this does not include inciting hate or violence). Given our members, we give special focus to the human rights situation of those who identify – or who are identified – as not subscribing to religious doctrine; but for us to genuinely defend the importance of the rights to free thought and expression we must highlight the abuse of such rights when it happens against anyone, not only to people without religion.

Readers familiar with the IHEU’s advocacy work will know we have spent much time at the UN calling out theocratic states on their abuse of the right to free thought, expression and their insistence on controlling women; whilst correlatively highlighting the merits of a type of legal and political secularism that helps human rights flourish. Interestingly, it is a framework that is never discussed by the Council, by the Office of the High Commissioner or by any other NGOs at the Council, so we have much work to do still.

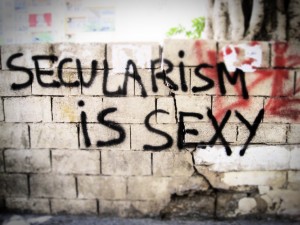

Of course, ‘secularism’ is not a straightforward concept and is relatively flexible in terms of its implementation. But I think we can agree that when we promote secularism, we do so because we believe it is part of a package of things – including democracy and rule of law – necessary to ensure equality and protect human rights. It is a means to best serve the demands of the rights to freedom of thought, expression and the rights of women, children and LGBTI people – i.e. those rights very often challenged by states, communities and people seeking to champion religion, tradition and culture instead.

So when we see those rights threatened and undermined in the name of secularism, I think it is very important that we stand up and say so.

When we hear Central Asian states, such as Tajikistan, banning beards and veils on the grounds of ‘secularism’ (in an uncomfortable mix with anti-extremist and pro-security rhetoric), we need to speak up. Secularism is there to serve human rights and fundamental freedoms, to help ensure equal treatment and remove prejudice, so when it is used to legitimise the undermining of such values, it is no longer the secularism we seek to defend.

When we hear talk from French authorities about “provocation,” “offence” and “public morals,” in terms of the ‘burkini’ we need to speak up. Not least because it perfectly echoes the type of rhetoric we have highlighted at the Council before in terms of being used by Islamic states as justification for enforcing conservative dress codes. No one who genuinely believes in the right to free expression can accept “provocation” or “offence” as a reason to accept its curtailment.[1]

It might be asked why we, as the IHEU, need to be the ones to highlight this issue with competition from the likes of Pakistan, Saudi, and Egypt and enthusiastic cries of Islamophobia, but I think it is essential. When we defend a woman’s right to express herself, we do it regardless of whether we like her opinions, regardless of her religion. Unlike those states whom we criticise, we must be genuine in our promotion of human rights for all; equally for those cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo and the woman on the beach who wants to cover her body entirely.

It might be asked why we, as the IHEU, need to be the ones to highlight this issue with competition from the likes of Pakistan, Saudi, and Egypt and enthusiastic cries of Islamophobia, but I think it is essential. When we defend a woman’s right to express herself, we do it regardless of whether we like her opinions, regardless of her religion. Unlike those states whom we criticise, we must be genuine in our promotion of human rights for all; equally for those cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo and the woman on the beach who wants to cover her body entirely.

Genuine freedom of expression and thought will never flourish unless we dispose of a tendency to highlight it only when it affects people who think like us, or say the things we wish to say.

We need to be different to those religious groups who talk about the abuse of rights only affecting people of their faith, those countries who only have a problem with offense when it comes from someone outside the accepted ideology. We need to be different: to defend freedom for all genuinely with impartiality and disinterest.

Properly understood, political and legal secularism is the best framework in which to ensure liberty, equality and human rights for all. Disproportionately limiting the right to freedom of expression through bans on clothing, veils or facial hair – particularly when targeted at one minority – devalues and debases this notion of secularism.

It is too much of an important value for us to let it be instrumentalised and misused for the tastes of the majority or oppressive control by government. In a climate of fear, and populism, of base catch-phrases meant to sooth the masses and scapegoat “the other,” genuine secularism is needed more than ever. We should own it, defend it, cherish it, stand up and say when it is being used wrongly. We need to say: Not in our name, not like this, No. Not in our name…

NOTES

[1] Incidentally, international law recognises the right of states to limit freedom of expression in the interest of “public morals”, but it is subject as always to the three-part test – according to which, limitations on freedom of expression must: 1) be provided by law, in sufficiently clear terms to make it foreseeable whether or not statements are permissible; 2) be directed at one of the following goals: ensuring respect of the rights or reputations of others, or protecting national security, public order, public health or public morals; and 3) be strictly necessary for the achievement of that goal, including that no suitable alternative measure exists which would be less harmful to freedom of expression.