For those of us monitoring the so-called “peace process” – mired as it was by the near complete exclusion of the democratically elected Afghan government, civil society and, particularly, Afghan women – the fact that the Taliban took over Afghanistan on 15 August 2021 came as little surprise. What did come as a surprise was the complete failure of the coalition forces to anticipate and prepare for it. Perhaps they were taken by surprise at the speed with which the Taliban gained control of the nation following the withdrawal of their troops on the ground, but the process itself took years of negotiation so one would have expected them to at least have put mechanisms of support in place for the most vulnerable.

While the situation for the non-religious in Afghanistan prior to the Taliban takeover was far from ideal, non-religious people reported that the rule of law afforded them a little more safety. They still, for the most part, concealed their beliefs, but did not fear being hunted down in quite the way that they do today.

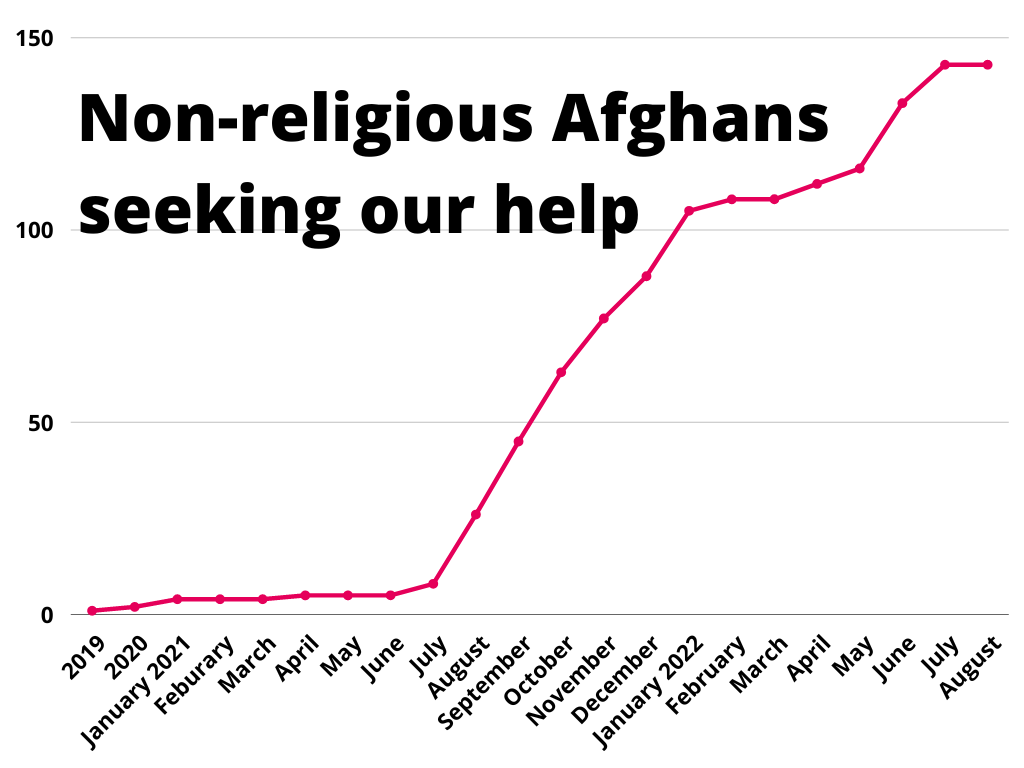

The cumulative total number of requests for help from non-religious Afghans

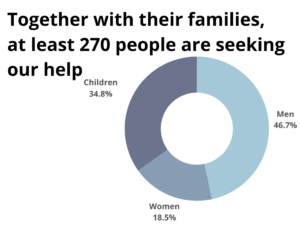

As the withdrawal of coalition forces approached, we began to receive a higher number of requests from non-religious people in Afghanistan – typically, people who had been outspoken on human rights issues and had a high profile. From 15 August onwards, I went from having two or three Afghan cases a year, to a request for help from an Afghan at risk every third day. They are often university professors (often in science), engineers, journalists, writers, women’s rights activists, doctors and students. Together with their families they amount to more than 270 people desperate for help.

According to the latest statistics, 16% of those who reach out to us are women. They are usually facing persecution for multiple and intersecting reasons, including their non-religious beliefs, gender, activism, or work as academics, medical professionals, and writers.

Behind each request is a person, many of whom have families that depend on them

Few of those who reach out to us have the financial resources to flee or maintain themselves abroad for a protracted period of time. The time taken to achieve relocation from a neighboring country often means that the situations of the individuals we are supporting are materially changing and in some cases becoming emergent. Children are being born in hiding; it was my honour to help name one such child, a beautiful little girl whose prospects should she remain in Afghanistan are grim.

The predominantly ethnic Pashtun Taliban emerged as a political force in 1996, when they took control of the capital Kabul and changed the name of the country from the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Their rule was characterised by the near-total exclusion of women from public life and strict application of Islamic law.

Leading up to the takeover, the Afghan Taliban received considerable assistance from Pakistan, where the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency has supported the Taliban from their inception with money, training, and weaponry.

Upon taking control of Kabul, the Taliban swiftly moved to reestablish the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, reinstating Sharia Law. On 7 September 2021, the Taliban announced an all-male caretaker government including an interior minister wanted by the FBI, as well as the reinstatement of the ministry for promotion of virtue and prevention of vice – a ministry dedicated to the enforcement of the Taliban’s extreme interpretation of Islamic law.

Within days, ethnic and religious minorities – particularly the Hazara community – were coming under increased pressure, facilitated by the fact that the Taliban authorities now have access to all biodata stored for its citizens and recorded on their identity documents. We have received reports of Taliban officials and their sympathisers conducting door-to-door raids. Demanding to speak to the head of households. I have seen photos of loved ones and friends killed; shot dead in the head because they were not religious.

The Taliban have sought out those who worked in government, with government agencies or security forces, including international actors. According to Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, “the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) continues to receive credible reports of arbitrary arrests and detention, ill-treatment and extra-judicial killings – particularly of persons associated with the former government and its institutions.”

In addition, despite promises to the contrary, the Afghan Taliban has embarked on a campaign to erase women and girls from public life. Afghanistan is now the only country in the world to ban girls from access to a secondary education. Decrees based on fundamentalist interpretations of Islamic principles deny women and girls their basic rights, including the freedom to travel alone, access services, healthcare, and mandate covering.

The response of the international community has been disappointing. Nine days after the Taliban takeover, the UN Human Rights Council held an emergency Special Session on “Serious human rights concerns and situation in Afghanistan,” the ultimate purpose of which was to come up with a resolution that helped bring about a human-rights led response to the crisis in the country. The end result was an anaemic resolution which Humanists International’s Director of Advocacy, Elizabeth O’Casey pointed out was laden with platitudes and empty words that, “failed to call for any concrete action, or dare even to mention the word “Taliban.”” It was not until 7 October that the UN Human Rights Council appointed a Special Rapporteur to investigate human rights abuses in Afghanistan.

Few States have successfully established functioning mechanisms for the evacuation of high priority applicants. While the bombing outside Kabul airport on 26 August 2021 brought official evacuations to a close. When employees and former contractors of coalition forces are still awaiting visa approval under priority schemes one year on, what hope does an ordinary citizen have?

Several governments announced special resettlement programmes for individuals belonging to specific protected categories, such as women, human rights defenders, and so-called “religious minorities”. The Canadian government’s work to resettle human rights defenders at risk should be seen as a gold standard; however, the mechanism is now oversubscribed and deserving candidates cannot gain access.

The use of the term “religious minority” led to ambiguity as to whether our community would be accepted among that number. Several of our Members and Associates have been instrumental in ensuring that their governments clarify that the non-religious would be included in this category.

Summary score data for Afghanistan and neighbouring countries drawn from the Freedom of Thought Report

However, a problem remains. Most resettlement schemes available to ordinary citizens require registration with the UNHCR. Afghans cannot register with the UNHCR within their own country, so they must be outside Afghanistan – typically they flee to neighbouring countries such as Pakistan and Iran. Neither are countries where one would wish to have their non-religious identity exposed. However, to qualify for resettlement, they must be identified as belonging to a religious minority group by the UNHCR.

To claim asylum as a result of the persecution they have faced or would likely face due to their non-religious beliefs would likely lead to even greater persecution in Pakistan, where the State, and local staff, is responsible for processing asylum claims. Members of religion or belief minority groups therefore find themselves in a Catch-22 situation, a solution to which has yet to be found.

Photo by Farid Ershad on Unsplash

If you believe every humanist should have the right to a life free from persecution, please show your solidarity and support with a donation today. With your support, we can continue to help as many people as possible in the weeks and months ahead.