The Covid-19 pandemic threatens the human right to health and to life, but the fear that a pandemic can inspire and the extreme measures it sometimes requires, risk undermining other fundamental rights. In this blog, Elizabeth O’Casey argues that our response must follow in the tradition of core humanist values by promoting human rights, universalism, evidence-based decision-making and an ethic of global solidarity.

The Coronavirus crisis has revealed a plethora of fault lines upon which our global community has been precariously built, and which have all too often been glossed over by those with money, power and privilege.

In it together? Not so much.

For a start, whilst the virus itself attacks anyone regardless of their status or privilege, clearly those suffering disproportionately from the pandemic and the measures put in place to tackle it, are vulnerable minorities and the poor. That is: people who are more likely to have health complications or can’t afford proper health care; people who lack the resources to stay at home for long periods or who live in crowded housing; people who have lowly paid jobs that force them to choose between potentially sacrificing their health or actually sacrificing their income; people without even basic sanitation; and people already fighting stigma or prejudice on other grounds (such as race, sexual orientation, gender identity, belief, caste, or disability).

Human Rights and rule of law under threat in the Covid-19 context

Not only are we seeing responses to the pandemic that penalise the already marginalised and disadvantaged, but the fear that a pandemic like this inspires (and is sometimes encouraged to inspire) and the extreme measures it sometimes requires provide fertile ground for power-hungry states to further undermine human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Some examples:

- The Hungarian parliament has passed a Coronavirus bill that gives Prime Minister Viktor Orbán the power to rule by decree and establishes chilling new penalties on speech and on those who violate quarantine.

- In Iran, authorities are reacting to protests in prisons over Covid-19 by using torture and ill-treatment that has resulted in extra-judicial killings. And despite freeing some prisoners, they have freed no prisoners of conscience.

- In the Philippines, the spread of Covid-19 has given law enforcement broad discretion to enforce public health measures, which has resulted in demeaning and dehumanizing treatment for vulnerable groups such as LGBTI individuals.

- In Venezuela, journalists reporting on the pandemic are detained, sometimes violently, and charged.

- In Poland, politicians attempted to sneak in a law (that would have almost completely banned abortion) at a time of lockdown when those who would usually protest on the street were banned from doing so.

- And in China, the State has weaponised confinement measures to silence and isolate any dissenting voices. Li Wenliang, the doctor who alerted his colleagues about Covid-19 – and eventually died from it – was censored and then detained for “spreading false rumours” and “severely disturbing the social order.”

And the abuse doesn’t just come from governments either; we have witnessed a spike in cases of prejudice, xenophobia, discrimination, violence, and racism against people of East Asian and Southeast Asian descent and appearance around the world. Reports of domestic violence have surged globally in the wake of massive lockdowns imposed to contain the spread of the disease.

Clearly, a human rights-oriented response is as urgent as ever.

The role of multilateralism and human rights

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and its independent experts have for the past few weeks been issuing excellent human rights guidance in relation to the pandemic and our response to it. The European Union’s Special Representative for Human Rights, Eamon Gilmore, wrote an excellent article underscoring the need for our response to be human rights oriented. It’s just a great shame that, meanwhile, other EU officials, after pressure from Beijing, have been busy watering down criticism of China in a report documenting how governments push disinformation about the pandemic, and that the only EU response to the Hungarian situation was a statement of “concern” from Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders. The EU has been positively inactive over Hungary’s blatant transgressions on rule of law and human rights standards for many years now, so no surprise there, I guess.

In addition to the response to the Covid-19 pandemic needing to be human-rights-centred however, is the need for the response to be global and collective in nature too. For all the many failings of our current multilateral system, it is all we have by way of solution; so, we need to fight for it, to fund it, to depoliticise it and to make it better.

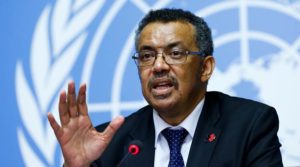

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Head of the WHO

We need a World Health Organisation whose approach and assessment is led by science, facts and human rights rather than one that is badly tainted by concerns of funding, political deals and rewards (the Chinese influence here and Ghebreyesus’s nomination of Robert Mugabe as a goodwill ambassador in 2017 both cases in point).

This may sound idealistic, since our multilateral fora are only as good as the members which constitute them or – as the previous UN High Commissioner for Human Rights said about the Human Rights Council – they can only be “as great or as pathetic as the prevailing state of the international scene at the time.” However, more funding and engagement from democratic countries with more of a commitment to human rights and accurately presented facts would be a good start. This is the essence of multilateralism: it is what we make of it, it is ours to shape and define together. So those who care should start shaping it. Money talks.

And where is the UN Security Council in all of this? During the Ebola crisis, the Security Council expanded its mandate by characterising a public health issue—i.e. the communicable disease Ebola— as a threat to international peace and security, which gave rise to the obligation for states to work in concert and prioritise international obligations as stipulated by the UN and WHO. It’s unclear why it hasn’t done the same with the Covid-19 pandemic.

Multilateralism, a rule-based international order and a robust space for civil society to scrutinise state action, despite all its problems, is the only way forward. This needs to be coupled with an unwavering commitment to any response to the pandemic being human rights compliant and grounded in evidence, science and solidarity.

Global solidarity and the power of science in the service of compassion

Our community has long advocated the application of scientific methods and free inquiry to the problems of human welfare. And whilst it is the science that gives us the means, it is the human values that must propose the ends.

We cannot allow this global crisis to be instrumentalised for the nefarious purposes of governments who seek to oppress their citizens, to undermine the rule of law and democracy. And we cannot allow the fear inculcated by the crisis to feed populism, nationalism and a rejection of those already on the margins.

We must instead take the opportunity to redress all the pre-existing injustices (such as inequality, discrimination, prejudice, poverty) which have been revealed in their rawest form through the patently unequal and disproportionate way some people have suffered from this pandemic (whilst others make money on their misery by insider trading…).